Are you familiar with the contexts defined by the Getting Things Done (GTD) methodology developed by David Allen? (e.g. @Home, @Office, etc.) If so, you may have discovered that the ones suggested in his book no longer fit your circumstances.

Even if you have already replaced them with contexts of your own, consider taking a deeper dive. Those offered by the author in 2001 were based on solid principles which haven’t changed. However, he did little to teach you how to select or design your own contexts.

Consequently, like most GTD’ers, you probably struggled for a while, trying to get the book’s contexts to work. At first, you may have thought there was something wrong with your comprehension of the idea. But no matter how much you read and reread Chapter 9, followed Allen’s subsequent explanations or sought the counsel of others, nothing clicked.

Eventually, you put together your own contexts, or abandoned their use altogether. But perhaps you have wondered: “Did I do the right thing?” Back in 2006 I asked myself the same thing, bouncing between several approaches within just a couple of years. All I could was try one after another, given my shallow understanding.

Perhaps you also lack an explanation of why contexts work, don’t work and whether they are even necessary. For you, this may be important as you look towards a future of even greater task loads, not less. Should contexts play a role in your task management, or not?

That’s why I’m writing this article – to provide you with some answers and, ultimately, a sense of relief. By the end, you’ll be able to use the same thought process David Allen used to choose contexts which work for you, regardless of your chosen task management system. This new appreciation builds on your current experience, giving you a path to follow.

THE BACKGROUND – A BREAKTHROUGH

When Getting Things Done: The Art of Stress-Free Productivity was published, the book introduced a major upgrade in the way you organize your to-do list. Once you got over the hump of not using your memory, you were taught to simply assign each task to a “context”.

In the initial edition, Allen explains contexts as the primary decision to make when sorting through your task list: “… the first thing to consider is, what could you possibly do, where you are, with the tools you have?” Among the “tools” he listed are @Phone, @Specific Persons and @Physical Location.

(For the sake of simplicity, I have ignored the @Waiting For and @Someday contexts in this discussion as they don’t follow Allen’s original definition.)

What benefits should result from this breakthrough approach? Here are three.

– When a single long list of to-do’s or tasks is broken down by context, you “prevent unnecessary re-assessments about what to do.” Fail to take this step and you are forced to scan all your tasks continuously, which becomes burdensome.

– When you happen to be within a particular context, you can take a shortcut by scanning other tasks which are tagged in the same way. For example, if you are in a meeting with your manager, you should check your @Boss list, thereby saving time and effort. Let’s call this convenience “contingent task planning.”

– Thinking in terms of contexts forces you to focus on the next action due to the challenge of confronting the physical resources required. It pushes you to be specific.

Other Criteria

But GTD goes further than recommending a list of contexts. It also suggests three other criteria when deciding what to work on next: time, energy and priority (in descending order of importance). At the same time, Allen only advocates the use of GTD-defined contexts in task management programs and paper lists. He does not use the tags related to time, energy or priority.

In summary, the book attempts to solve the question of: “How do I decide what to work on in the next moment?” Obviously, it’s impossible to complete an action which requires a tool or tangible resource which is missing. That observation may explain why physical context figures so prominently in his thinking.

Also, Getting Things Done does a great job of describing the benefits of using tags in “contingent task planning”. However, it hardly mentions their use in the important job of “primary task planning”. That is, how do you select which context to place yourself in tomorrow, next week or next month? Now, in 2021, you are contending with 24 hour per day and 168 hour per week barriers which cannot be violated. Tags can help you overcome this challenge.

WHAT HAPPENS WHEN THINGS CHANGE?

As we near the 20th anniversary of GTD’s publication, is it fair to say that life is very different?

1) The mobile, high-speed Internet has allowed us to gain unprecedented access to phones, people and remote physical locations. Now, we can do much more, regardless of where we are.

2) COVID-19 has sparked the rise of working from home. No longer do we need separate @Home and @Office contexts.

3) Other technology improvements place amazing computing power at our fingertips just waiting to be tapped via our smartphones, PC’s, tablets, televisions, game consoles, cloud networks, etc.

As a result of these changes, many GTD’ers have abandoned Allen’s original contexts. However, the book fails to give any indication about what to do next. This conundrum is where our discussion really begins. Our goal in this article is to devise ways to organize our tasks so we are effective not only in 2021 but also in 2050 or any point in the future. We are on the hunt for enduring, practical principles.

UNDERSTANDING WHY CONTEXTS WORKED

To get underneath and behind the specific recommendations Allen originally made, we need to understand a few timeless principles that GTD doesn’t quite explain, but relies on.

Principle 1 – Human beings started creating tasks long before the first mechanical clocks were invented in the Middle Ages. In fact, a task happens to be a psychological object with peculiar properties.

What does that mean? When a task is born in your mind, it includes with it a number of attributes. These arise at the moment of creation. They address whatever concerns are uppermost for you, such as the task’s importance, duration, location, cost, and likely time of execution.

Most of these attributes sit in the subconscious, hidden from view. However, a few are made explicit by systems like GTD, which call for you to tag them once you need to work with them.

Case in point (a): You may have noticed that after reading Getting Things Done, you became extremely aware of each task’s context. Perhaps (at first) you entered this particular tag in your software, apps, and/or paper planner lists.

Case in point (b): After reading First Things First by Stephen Covey, many readers become aware of two specific tags he borrowed from the Eisenhower Matrix: importance and urgency.

As such, Allen, Covey and Eisenhower didn’t invent task attributes. Instead, these thought leaders helped you extract them from your subconscious. They recommend that you bring them out and make them explicit, where you can benefit from their existence.

Principle 2 – The second unstated rule is that the technique of tagging should be used sparingly. In other words, it doesn’t help to add every imaginable tag to your tasks.

Why?

The overhead of managing too many tags quickly becomes unbearable, even with the best-made software or the smartest administrative assistant at your disposal. GTD implicitly recognizes this problem and urges the user to effectively ignore all tags except context.

Therefore, any system you use should seek to minimize the number of tags, treating them as a useful but necessary evil.

Principle 3 – Getting Things Done offers a number of novel solutions to hard-to-solve problems which were outstanding in 2001, but have a different shape today.

For example, almost everyone accepts that the use of personal memory for task management is a bad idea. However, the average 10 or 11-year-old who has only one or two things to remember each day need not read GTD. Instead, their use of memory might be sufficient.

The same phenomenon occurs for some retirees. They are managing dramatically fewer demands on their time. Neither paper lists nor apps are necessary. They have reverted to the use of what psychologists call “prospective memory”, the kind of remembering we engage for future activities.

These discoveries negate none of GTD’s core message, but they do suggest a more nuanced picture. As I explained in Perfect Time-Based Productivity, Allen’s suggestions are tailor made for individuals who are in one of two special situations, but not for everyone.

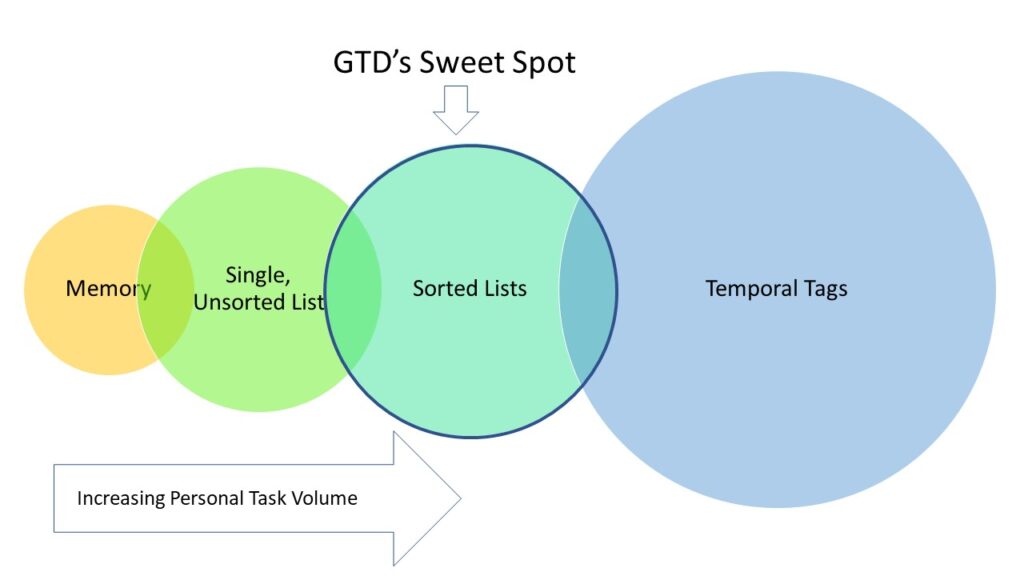

In general, the book was written for professionals who use either memory, or a single, unsorted task list AND experience unwanted symptoms as a result. Why do these people have issues, and not the 10-year-olds or retirees mentioned earlier?

It’s because there’s a mismatch between the tool they are using and the volume of tasks they are trying to manage.

To illustrate, imagine moving a hill of dirt with only a hand trowel and the relief you feel when you discover improved tools are available. You wouldn’t hesitate to pick up a shovel, borrow a wheelbarrow, or rent an earth-mover once you know these alternatives exist.

Now, consider the individual who is using memory or a single, unsorted task list. These techniques actually work just fine for a limited number of tasks. Their users don’t experience errors and other unwanted symptoms.

However, GTD targets those individuals whose task volume exceeds the capacity of these two approaches. The sense of relief they share is real: there is a way to escape the limitations of the tools and techniques they have been using.

But that’s not the end of the story.

Is there also a limit to the application of Getting Things Done? In other words, is the approach ideal for a given volume of tasks… but an impediment above a certain threshold? And if there is such a threshold, what should one use once it’s exceeded?

We’ll answer this question in the next few paragraphs.

WHY AND WHEN GTD’S CONTEXTS FAIL

If the final principle stated above holds any merit, how does it apply to the use of contexts, or the broader use of tags?

As we have seen, the contexts offered in the first edition are a tiny subset of the attributes we can make explicit. That reasoning seems logical. But does its application need to evolve when our environment changes? Or more to the point, has this already happened?

Given that many GTD’ers are no longer using the first edition’s suggested contexts, are they now useless? Or are we making a mistake by not using them?

Well, if we follow the three timeless principles behind GTD’s approach, the answer is…it depends. In fact, here are four possible responses among many to the question: “Should someone use the contexts from Getting Things Done?”

Answer #1 for the 10 to 11-year-old child or the retiree: They may have no use for contexts if their personal memory is sufficient.

Answer #2 for the one single, unsorted list-maker: This person may have no use for contexts if their chosen combination of tool and technique gets the job done.

Answer #3 for the busy professional who can no longer use memory or a single, unsorted list effectively: GTD provides an excellent solution.

Answer #4 for the hyper-busy over-achiever who routinely has no free time: Tagging tasks using temporal attributes is far superior to the way GTD uses its contexts.

In other words, contexts are best used when someone is trying to manage a particular task volume – there’s a “sweet spot”. Conversely, at higher or lower volumes, the approach is not the best choice.

In fact, according to the above diagram, no single choice of practice + tool is ideal. Instead, they each have their ideal range, even when there is some overlap.

This is a more nuanced picture than the book offers. However, it’s built on the same principles but taken a step further. It rejects the idea that contexts should always be the top criterion used when deciding what to do next. Instead, there are other alternatives.

In the original 2001 book, Allen explicitly argues against using time-based tags, and the resulting practice of placing tasks in one’s calendar. (Today, the technique is known as “time-blocking”, “calendar blocking”, or “time boxing”.) Readers who took his words literally have remained stuck, even as his thinking has evolved.

THE EMERGENCE OF TEMPORAL TAGGING

What should someone who gives Answer #4 do differently? Well, instead of tagging their tasks using contexts, they would use temporal attributes. Some examples include duration, start time, due date, biorhythm, and “monotaskability”. (The latter relates to the degree to which one can effectively undertake two tasks at the same time, such as “walking and chewing gum” at one extreme, versus “texting and driving” at the other.)

Someone in this category would naturally gravitate towards habits like time blocking and time tracking. Their use of tools like calendars, auto-schedulers, administrative assistants, and time maps becomes second-nature. While they will always experience a chronic lack of “free” or discretionary time, they are forced to program breaks in order to have a balanced life.

Others advise these high-achievers that they are trying to do too much and should cut back on their task volumes. A more fruitful response is to encourage them to look to the future, and the advent of innovative habits, practices, routines, apps, tools, devices and administrative assistance. These will be specifically designed to help them manage even more tasks.

THE NEW CONTEXTS

But what about the busy professional who chooses Answer #3? This response represents the majority of GTD users, for whom there is no need to switch to temporal tagging. Instead, if you fall in this category, you may only require a modern approach to replace the standard use of contexts. To find solutions, let’s attack the question using the three unstated principles.

(For the sake of clarity, I’ll avoid any reference to temporal tags whatsoever, such as weekends, evenings, or tomorrow. I will explain how they can be incorporated later.)

As I mentioned, there are always an array of tags to select from your subconscious list. How many? There are new suggestions every day, which means that the list is probably infinite. (Here is a link to a download of a brainstormed set of attributes plus their suggested values.)

But more importantly, how should you decide which tags to use? What are the reasons to choose one tag, or some tags, over the others?

If we take a close look at the contexts GTD suggests, we may agree that David Allen selected the ones which mostly represent the scarcest attribute he could find first-hand: physical resources.

My research suggests a universal Task Tagging Rule: When choosing tags, always pick ones which correspond to the scarcest resources you can identify. Also, pick the fewest number.

In your case, how can you identify which resources are the scarcest?

Ultimately, you require an in-depth evaluation of your current setup, and the places and moments where you experience problems in your task management. Here are some possible examples, followed by some values they could take.

Example #1 – Flow State – Hi / Med / Lo / n/a

Example #2 – Cash – Free, $1-500, $501-1000, $1001-5000, $5001+

Example #3 – Manpower – Solo, Partner, Trio, Four +

Example #4 – Energy/Strength – Hi / Med / Lo

Example #5 – Mentality – Work, Vacation, Holiday, Weekend, Evening

Example #6 – Profitability – Hi / Med / Lo

(Remember, here is a brainstormed list of tags you can download.)

When you identify the scarce resource, apply the tags in the same way Getting Things Done uses contexts: as a method to focus your attention on a subset of all your tasks.

How many tags should you use?

My recommendation is to start with a single, primary tag for all your tasks. Experiment to see how well it fits your needs. Only if you experience a significant shortfall, consider an additional, secondary tag.

I suspect that if you find yourself wanting tertiary tags (or more), you probably should consider an upgrade to temporal tagging. If this is the case, check out my book and the resources at ScheduleU.org.

It may also be time to consider temporal tagging if you find yourself wanting to make more detailed schedules than Getting Things Done recommends. This becomes a natural concern for people whose task load keeps increasing. At some point (for them), the benefits of “contingent task planning” are dwarfed by the gains to be made by “primary task planning”.

In other words, your decisions to place yourself in particular contexts tomorrow, next week or next month are, generally, far more important than the secondary tasks you happen to perform while in those contexts. For example, your core decision to spend next week Friday in either @Plane, @LA Office or @Home NYC is more critical than the tasks you find it convenient to complete because you happen to be in a given location.

It’s the difference between worrying about what you should do while on vacation versus making the multi-faceted decision to go in the first place.

Unfortunately, the better you follow Getting Things Done, the more likely you are to use the benefits to increase your task volume. As you feed off your success, your free time disappears, and time-based tradeoffs become more difficult to make.

To help you navigate this predictable challenge, start using rudimentary temporal tags such as @Tomorrow, @Next Week and @Weekend. They’ll help you begin to make the mental shift required if you are new to temporal tagging.

A FINAL NOTE OF CAUTION

If you’re like most people, you may not need to change anything in your current setup right away. Bookmark this article for a time when you require it.

Or you may require some immediate changes. Perhaps you are experiencing significant unwanted symptoms and are committed to handle more tasks effectively.

The challenge you face is to determine the magnitude of the shift. For example, if you are currently using contexts, do you need better tags for your lists (Answer #3), or require a switch to temporal tagging (Answer #4)?

I can’t answer for you, but I do recommend you be somewhat cautious. Tinkering with your task management system is a real-time experiment. It’s a bit like changing a wing while you’re still flying the plane.

Proceed at your own pace, and maybe use the resources in Perfect Time-Based Productivity to get a better understanding of your current habits, practices, tools and devices. That assistance could give you the insight you need to proceed with some confidence.

SUMMARY

While GTD doesn’t offer much help in migrating from its suggested use of contexts, its success is based on sound principles. If there were a science of task management, David Allen’s work would be seen as a great start.

However, the onus is on the reader to go the extra mile and choose the tags which make the most sense, given a particular task volume. This evergreen approach will last the test of time and give you both power and flexibility.

To discuss this article on Twitter, ping me at @2timelabs.

Coming next in the series: How to Transition from Contexts to Temporal Tags

References: Perfect Time-Based Productivity

Getting Things Done – The Art of Stress-Free Productivity

This article also appears on Medium, as voice recordings on a podcast and on YouTube.

Update: A few weeks after this article was published, I offered a free webinar. The replay is available here.